-100–

July on Kojima was wonderful. As the air grew hotter, the sea warmed up as well, and on sunny days I swam almost daily. My routine was simple: wake up and dive into the sea, practice until nearly noon, head to the mainland for lunch and groceries, return to Kojima around 4 p.m., walk home and work up a sweat, then cool off with another dive in the sea before taking a shower and resuming practice.

In contrast, my progress on the silent bass was discouraging, to the point where it felt almost depressing. I had never before felt an aversion to even picking up the instrument, but I found myself stuck in a plateau with my right-hand pizzicato, and I could not bear to record my playing. Last month I thought I was finally beginning to see a horizon for my right-hand technique, but it turned out I was not even close. Day after day I wrestled with improvements that never came. My rhythm and tone collapsed so badly that listening back to my own playing was painful.

To make matters worse, I had painted my silent bass black, and the sound deteriorated further, making practice even harder to face. I suspect the cause was the acrylic oil stain I used. Compared to lacquer or dye-based finishes, it leaves a thicker coat, and I believe that prevented the wood from resonating properly. I never imagined a single paint job could change the sound so drastically. I had once thought claims about finish affecting tone were nothing but myths spread by material purists. But the difference was undeniable: compared with before painting, the sustain had clearly died. Perhaps I am the only fool in the world who would take a 380,000 yen instrument and ruin it with his own paint.

The sound had deteriorated so badly that in the end I spent more than a full day sanding off the finish I had applied. To my surprise, the tone almost completely recovered to its pre-finish state. The connection between finish and sound runs deep. Now the bass looks as if it has just come out of a fire site, scarred and raw. I have promised myself not to repeat the same mistake again. Next time, I plan to refinish it with TransTint Black Dye and a thin coat of Tru-Oil, keeping the layer as light as possible.

When it comes to practicing the double bass, I had always felt that the more I practiced, the more progress I made, and for that reason I never once felt an aversion to playing the instrument itself. But mastering three-finger pizzicato on the double bass is extremely difficult. If I try to use the same approach as with two fingers, angling them so more surface area makes contact with the string to draw out maximum sound, my fingers do not function properly. It has become clear to me that the electric bass and the double bass are entirely different instruments. On the double bass, you must search for the sound directly from the fingerboard, which forces you to study theory. At the same time, you are constantly pushed into a dialogue with yourself: how to relax the body and produce the greatest sound with the least energy.

Interestingly, my right hand on the electric bass has advanced beyond my previous two-finger pizzicato level, even though I have not touched the instrument at all. Simply by pursuing pizzicato on the double bass, my electric bass playing has improved. I have finally reached the point where I can express the phrases I want, which led me to a chance to perform solo in front of an audience on the Hinase mainland. Playing the bass guitar alone in a way that communicates clearly to listeners is no easy task, but the experience has been full of lessons. Most of all, I realized that harmony and rhythm must be controlled perfectly. For harmony, I had to internalize chord progressions well enough to outline them through triads, and for rhythm, I needed to craft clear phrases that made the pulse easy to feel. These solo opportunities have become invaluable practice. Perhaps in reality, it is simply the lack of friends nearby to make music with, but I try to see that reality through a positive lens.

In July, I continued listening to Chris Potter as much as ever. I suspect I will need a few more months to really take it all in. Each of his pieces contains so much information that my ears cannot possibly process it in just one month. For transcription, I stayed with Charlie Parker again, this time working on Bird of Paradise. My aim was to grasp the way he feels rhythm in triplet phrases, as well as the descending lines where he makes heavy use of chromaticism.

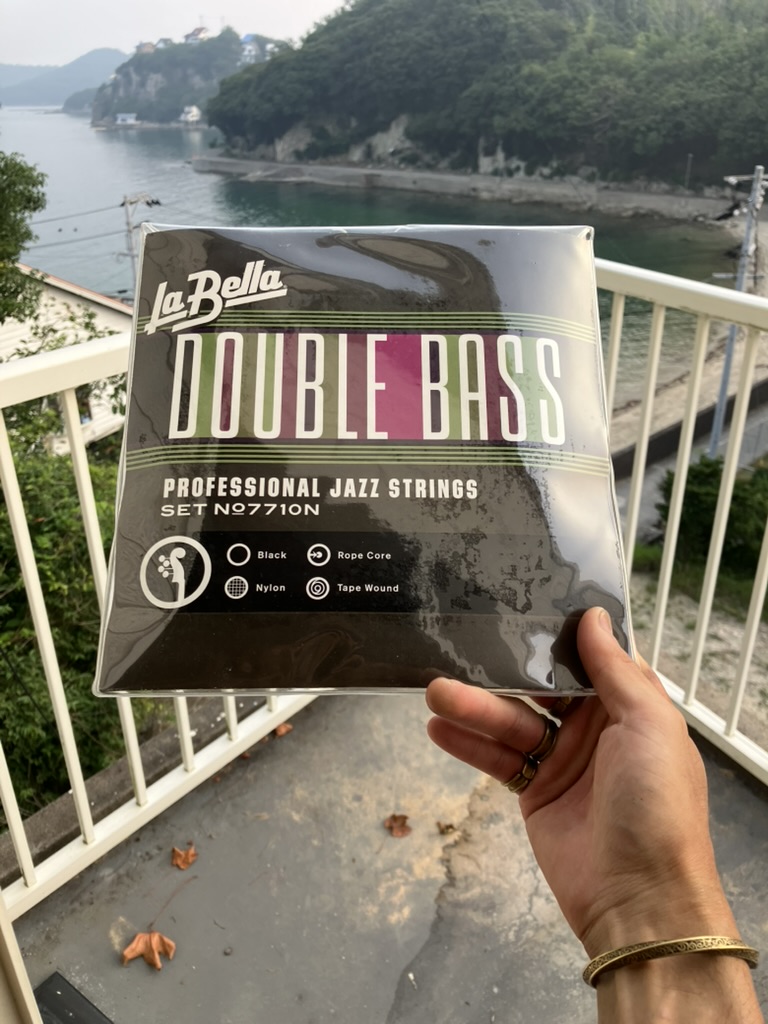

La Bella Black Nylon Strings

Since I ruined the sound of my silent bass by painting it black, I am not sure I can give them a completely fair evaluation, but I recently bought and tried La Bella’s Black Nylon strings (7710N). I had tried them once back in my university days. At that time my double bass setup had issues, and combined with the naturally high tension of nylon strings, I remember they were almost unplayable.

My current silent bass setup is relatively low action, so I thought it would be a good chance to revisit these higher-tension strings. The Thomastik Spirocores I have been using so far have very loose tension, which makes pizzicato easy to play, and they produce a bright sound with long sustain. However, compared with the G and D strings, the A and E strings of the Spirocores sound much darker, to the point of feeling unbalanced. That imbalance led me to try the Black Nylon strings, hoping they would deliver a brighter tone on the E and A strings, even in higher positions.

Conclusion; after using them for a month, I realized that the La Bella Black Nylon strings are not for me. It is true that the E and A strings sounded brighter than the Spirocores, just as I expected. However, also as expected, the higher tension made pizzicato harder to play. I also felt the sustain was shorter than the Spirocores. For example, playing in higher positions above the three-octave G made the difference very clear, with the Spirocores sustaining much longer.

For the foreseeable future, I will likely not move away from Spirocores. If anything, I might be curious to try the E and A strings of the Helicore Pizzicato set, but since they also have more tension than Spirocores, I suspect I would end up with the same impression I had of the Black Nylon strings: the tone may be bright, but the feel on the fingers makes them harder to play.

Shopping in Ochanomizu, Tokyo

In July, I spent about five days back in Chiba to meet up with friends. While I was there, I stopped by Ochanomizu to look for a good bass guitar. I tried out several different instruments, but once again I found that Japanese-made Fender-style Jazz Basses are not for me. Not only did they lack resonance, but their sound also felt generic, without any real character.

On the other hand, the instruments that impressed me far more than I expected were a maple-fingerboard model of Fender Mexico, and a similar type made by the brand SX. Both had a clearly defined tone with a strong outline, and they resonated beautifully.

Among all the instruments I tried, the one that surprised me most was the Yamaha BX-1. I had never played a headless bass guitar before, but I found myself wanting one. Since carrying my SELDER bass back and forth between the island and the mainland puts a strain on my shoulder, I had been looking for a lighter instrument, so it caught my interest. Still, from its appearance, I did not expect it to have much physical resonance in the wood, and so I had little hope for its sound.

The Yamaha BX-1 was a bass I decided to buy the instant I played it. I had never before encountered such a small-bodied instrument that resonated so well. The sustain was long, the sound leaned bright, and the U-shaped neck was easy to play (perhaps it might actually be a medium C-shape). Playing on a U-shape neck made me realize how flat and lifeless the fingerboards and necks of other basses can feel, as if they were nothing more than flat boards glued together.

While I was there, I also tried a headless Steinberger priced at over 200,000 yen, but it hardly resonated at all and felt difficult to play. Perhaps the setup was poor, but either way, the BX-1 left me with a positive sense of surprise.

Back on the island, I compared it with my two other bass guitars. Despite having the smallest body of the three, the BX-1 produced the strongest resonance. This feeling continues to puzzle me. Is it because of good wood, because it is finished in lacquer, or because it is a vintage instrument that has been played in over the years? I still cannot pinpoint exactly what determines the sound. And that, to me, is part of what makes bass guitars endlessly fascinating.