When November arrived, Ko-island suddenly turned cold.

It felt as if one day was still summer, and the very next day winter had already begun. Because of this abnormal seasonal shift, a Japanese restaurant owner I often visit told me that the local specialty oysters from Hinase, Okayama, the closest town to Ko-island, were reduced by about fifty percent. The cause is believed to be the unusually high sea temperatures this year.

In mid November, I tried swimming in the sea once, wearing a wetsuit. During the first minute, I honestly thought my heart might stop. As I kept swimming desperately, my body gradually adjusted, and I realized I could manage about twenty minutes. Still, when I dove underwater, the cold felt much more intense. It works well as a wake up shock, so I might add it to my routine on sunny days.

Because the temperature change arrived so suddenly, I was told by island residents that the trees on Ko-island are changing their colors later than usual this year.

In early November, I was in the Kanto area, in Chiba. I took time off work and stayed there for about two weeks starting in late October. After getting used to life on Ko-island, visiting the city again made me realize how different the lifestyles are. I became aware of the quality of the air and the level of noise. Living in nature strengthens the survival side of oneself, yet at the same time it sharpens the senses so much that, in a way, it also makes one more fragile.

After returning to Ko-island from Kanto, I spent much of my time practicing and going to jam sessions. My practice focus had not changed for the past six months, concentrating on improving my right-hand three-finger technique and transcribing solos. With the three-finger technique, I have finally begun to get used to using my right thumb as a pivot, applying torque and letting the weight of my arm sink into the pizzicato. Once you adapt to this approach, it becomes unbearable to listen to the tone of my older recorded pizzicato. I can’t help but feel that I should have realized this much earlier. At the same time, I still feel some awkwardness when moving across strings, especially on the A string or when shifting between strings. There is no solution for this except to keep working at it over time. When trying to improve a single musical issue, long-term, repetitive practice becomes unavoidable, and that reality inevitably forces humility.

December on Ko-island is cold. Even so, the temperature rarely drops below zero at night, and compared to summer, the climate feels relatively stable. There are no sudden rain, and there are many clear days. Still, I no longer feel like swimming in the sea, although there are moments during the daytime, around 2 to 3 p.m. when the sun is out, when I walk slowly along the shore half dressed.

Because there were many public holidays in November, weekend guests stayed on Ko-island from time to time. On the other hand, in early and mid December, no one came at all. There were, however, a fair number of reservations scheduled for the year-end and New Year period. Going to jam sessions and talking with people, as well as responding to guests, sometimes feels essential for remaining socially functional.

In December, it starts getting dark after 4:30 p.m. At least where I live, the position of the trees blocks the setting sun, which shortens the time during which vitamin D can be produced. Since it is cold outside, when I do not move my body much, work indoors, and meet no one, I begin to feel as though part of my brain is deteriorating. I cannot help but sense that a program called loneliness is installed in our hardware by default. For that reason, I was genuinely happy when my friends came to visit for a few days in mid December.

Barbecuing in winter, and lying on the pier while looking up at the sky filled with stars, became memories I will not forget.

The black smoky looking object in the middle is a burnt onion.

As the season turned to winter, I began to notice something. When I observe the night sky from the pier, I sometimes see countless tiny creatures in the sea below, flashing and glowing at a speed like blinking. As I looked into what they might be, I found that they were neither sea fireflies, nor noctiluca, nor flashlight fish. The closest match seems to be something similar to a lanternfish.

When I scoop up seawater in a cup, tiny transparent fish glow inside it, although they are difficult to see clearly in this photo.

At least in real life, they are transparent and less than one centimeter in size, emitting pale blue light in random patterns. Their glow is incredibly beautiful. When I grow tired of watching the stars, I look down at this chaotic electrical parade, and when I tire of that, I return to gazing at the night sky again. Occasionally, squid emit red or yellow light, making the surface of the sea at night surprisingly lively during this season.

The atmosphere of local jam sessions in Japan

Since mid August this year, whenever I was in Okayama, I made a habit of going to some kind of jam session every week, whether in Okayama, Hyogo, or Kagawa. As I did so, I gradually began to notice certain universal patterns, both in the differences from the jam sessions I experienced in Minneapolis before 2018 and in the way Japanese musicians tend to think.

At almost every session, there is a welcoming atmosphere even among people meeting for the first time, built on the shared understanding that everyone simply loves music. That part is something I truly appreciate. At the same time, I also noticed that in some places musicians do not actively exchange information with one another. This tendency becomes stronger as the average age of the participants increases.

I also realized that there are spaces where musicians are encouraged to freely play a wide variety of music, while in contrast, there is another group of musicians who believe that only performances based on traditional values should be considered jazz. In addition, the order of performers is often decided in advance, and spontaneous sit-ins rarely happen. Because of this, I cannot help but sense a karaoke-like element. In particular, there are many people in their fifties or older who want to sing only the theme of a jazz tune, which made me realize how deeply jazz melodies are loved even in regional areas. When a predetermined order overlaps with people singing only the theme, there are moments when I feel as though I am standing in a karaoke venue.

At the same time, having a fixed order allows each participant to choose the tunes they want to play. This makes it possible to test pieces that feel challenging in what becomes a kind of β-version testing ground. In that sense, it is interesting in its own way. When I was in the United States, I remember that participating as a bassist meant I rarely had the freedom to decide such things myself. I have also been told by other musicians that even in Tokyo jam sessions, players in the rhythm section are almost never the ones who choose the tunes.

In many cases, people tend to expect someone else to take the lead, which reflects a distinctly Japanese characteristic of being considerate toward those around them. Because of this, I have had opportunities to reexamine when I myself need to step forward and take initiative depending on the situation, and that has been a valuable learning experience.

I also find it interesting to listen to other musicians exchanging thoughts about good music during jam sessions. It is not so much the content of the conversations themselves, but rather the fact that the space allows people across different generations to say things like, “The music I listened to recently was really good.” There is something deeply appealing about that kind of environment.

Life in a tent

When I attend jam sessions for several days in a row, returning to the island starts to feel troublesome, so I tend to stay in the city. Back in August, when I first began going to sessions regularly, there were times when I slept for six or seven hours at internet cafes, paying around 3,000 yen. However, on Fridays, places in Okayama and Himeji often fill up, which requires advance reservations. Check-in can be bothersome, and sharing air with strangers began to feel unhygienic to me, so I started bringing a tent more often.

After sessions, when people ask me where I plan to stay and I answer, “I’ll pitch a tent in the park right over there,” they usually look surprised. Especially as the outside temperature drops and insects disappear, life in a tent feels extremely comfortable, although from a general perspective it may look like the lifestyle of an ascetic monk.

Since I enjoy winter mountaineering, checking into a city park at around zero degrees does not feel inconvenient at all. Setting up the tent and mat takes less than about ten minutes, and simply owning a full set of winter-mountain gear makes life feel as though it has more possible paths. That sense of expanded choice is deeply appealing to me.

The tent I use is a single wall, X-frame model made by CRUX, developed for alpine environments. It takes less than three minutes to set up, since all you need to do is run two poles through one large piece of fabric. Most tents used for ordinary camping have a double-wall design to prevent condensation. CRUX, however, uses a special breathable material, so condensation does not occur except in rainy conditions or when two people sleep inside the tent.

Likewise, the winter-grade ThermaRest mattress, the X-Therm, is designed to block cold from the ground and reflect body heat, which keeps it very warm. Because the mat itself is overkill, there is no need to bring a large expedition-level sleeping bag. A backpack of around 30 liters is enough, which makes the system highly portable.

The tent also has strong wind resistance, and because it does not have many ventilation openings, as long as I wear my full down setup, I do not feel cold inside at all. In fact, living in a tent during summer is far worse.

A hammock combined with an underquilt, a down layer attached beneath the hammock, would probably be comfortable enough for sleeping in the city as well. However, the parks where I usually check in are typically located in residential areas surrounded by apartment buildings, which means there are not many trees.

Stealth camping in neighborhood parks works well. In parks that are relatively well known, there is sometimes an added wake up service in the form of extremely loud radio calisthenics starting around 6:30 a.m., which makes earplugs essential. Because of this, I have recently tended to avoid those places.

As a result, I realized that the optimal solution is to look on Google Maps for small, obscure parks tucked away in the corners of residential neighborhoods that no one really knows about. Since I can pack everything up within ten minutes and check out early in the morning, the working residents of nearby apartments or houses would never notice that someone had spent the night outdoors nearby on a weekday morning.

Encounters with music lovers in Okayama

I was surprised to discover how many people in Okayama truly love music. One of them is a friend who comes to Ko-island every day for work as a kind of handyman and is also a dedicated record collector. Through him, I was introduced to various bars around the city. In these places, turntables and vinyl records are casually set up, and people who organize music events often stop by. A deep and living music scene exists within Okayama.

They introduced me to a wide range of music, from global sounds to avant-garde works and spiritual styles. Before coming to Okayama, I had not even realized that genres such as ambient or noise existed. As a result, my personal music library has expanded rapidly over the past year.

In particular, when I invite my friend, the record collector, to where I live and we listen to music together while exchanging thoughts, I cannot help but realize how narrow my own world within the vast framework of music has been. When most of one’s time is devoted to improvisation, it is easy to fall into the illusion that improvisation itself is the core of music. In reality, improvisation is only one element among many, and I have begun to sense how easily composition, tone, and other elements can be overlooked.

Perhaps the era I am living in also plays a role. In a time when face to face communication is gradually thinning due to technological development, we can listen to endless amounts of music through streaming. When opening social media, especially within the jazz community, attention tends to gather around content that emphasizes the acrobatic or athletic aspects of improvisation. Because of this, I had lost sight of thinking about music from a broader structural perspective.

When I spend time with people who simply love the experience of listening to many kinds of music, I am naturally brought back to the larger framework of music itself, and to the question of what truly makes good music. Through that process, I find myself able to step back and reflect once again on my own improvisation.

At times, I find myself unsure whether I truly love music, or whether what I love is improvisation itself. Listening to Coltrane’s live recordings may be similar to the pleasure of watching a jester performing outrageous acrobatics in a palace or a circus. Jazz musicians who play improvised music each seem to possess their own unique, almost comic book like superpowers, and perhaps those of us who listen are simply searching for the joy of discovering them.

Yet the act of improvisation, as a process of choosing sounds, inevitably forces one to confront an ego that wants to stand out or be noticed, something that is not essential to making music. Because of this, it becomes necessary to remain aware of not being dominated by that impulse.

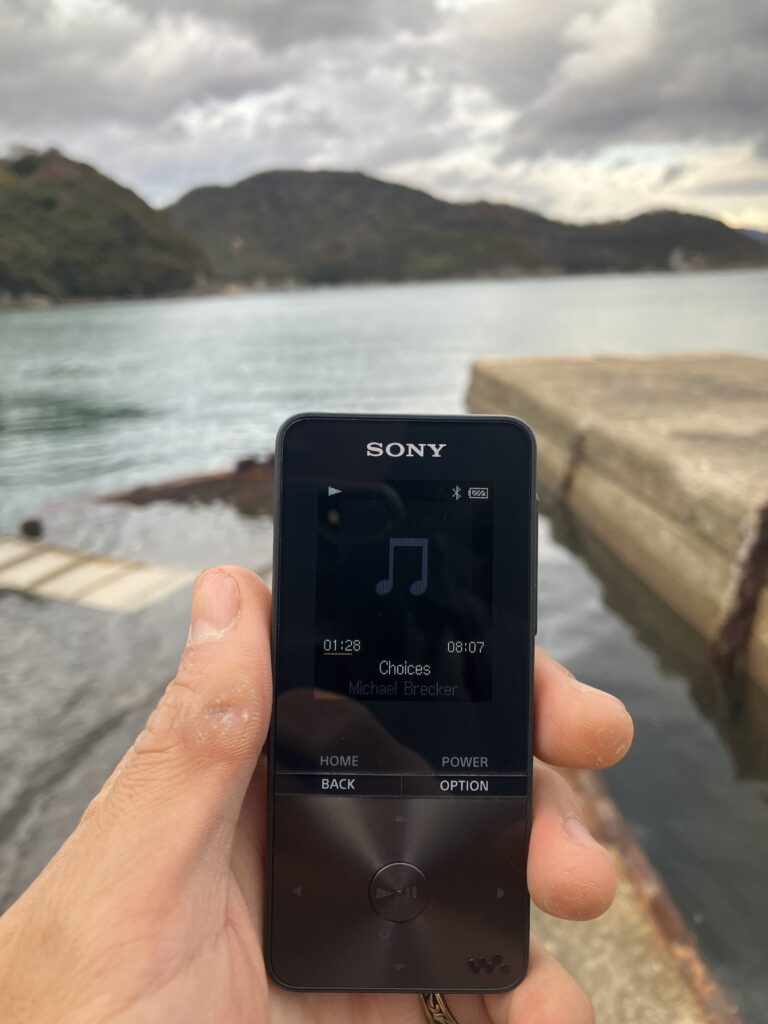

MP3 Player

Through spending time with friends who come to Ko-island for work and with other music lovers who regularly use vinyl records, I have come to realize how important it is to actually own media. Owning it allows one to commit more deeply to listening.

Since moving to Okayama Prefecture, there was something that surprised me when I visited a record shop together with music loving friends. On the front and back of album jackets, not only are the participating artists listed, but the background of how the music was created is often written as well. This adds a new layer of information to the listening experience.

I have many frustrations with modern streaming services. Of course, there are issues such as artist exploitation, AI-generated generic music, and algorithm-driven recommendations. But as someone who mainly listens to jazz, what troubles me most is that there is almost no information about the musicians who contributed to each track. I recall Hiromi Uehara once saying on YouTube that it would be convenient if streaming services had an information button, something you could tap to see the participating artists.

Searching on Google is tedious, and the information always needs to be carefully verified. Relying on ChatGPT also feels uncomfortable, since the reliability of the information is not guaranteed. If searching an album title leads directly to a Wikipedia page, that is fine, but many individual tracks do not have such documentation.

As a result, while streaming allows me to listen to the songs I like, it does not tell me who contributed to them or how the album came together. This makes the historical context and horizontal connections between musicians unclear. I believe that learning jazz, and music in general, requires understanding not only the sound itself but also its history and roots. For that reason, I came to feel that listening should be done on an album-by-album basis.

Because of this, I decided to buy an MP3 player. I considered an iPod, a Walkman, and several inexpensive Chinese made options. However, taking into account durability and the need for Bluetooth, the Walkman was essentially the only realistic choice, so I went with that.

At last, I feel freed from the state of media “non-ownership.” Listening to music on a Walkman is completely different from the experience of streaming. First, I research the music I want, download it, organize it into folders on my computer, connect the Walkman, and only after dragging and dropping the files am I finally able to listen. This process may seem inconvenient, yet it creates a sense of attachment to the music. By building my own personal library, my preferences become visible to me.

Even though the listening experience is different, the sound itself does not actually change, although high-end MP3 players may offer better audio quality. Still, I have come to feel that listening to music is not simply about hearing songs. The entire process of intentionally choosing which tracks to place onto a device with limited storage feels like a commitment to each piece of music.

Another advantage is that when I go for a walk, I do not need to carry a smartphone that constantly sends notifications. Modern smartphones have begun to resemble a kind of drug. When I think about how much of our time they try to steal before we even reach the point of playing the music we want on a streaming platform, it feels unsettling. And once a song finishes, the next track that tends to play is often Oscar Peterson or Paul Desmond. These choices are likely driven by a logic that favors easy listening and broadly appealing tracks.

Michael Brecker Biography

I began reading Brecker’s biography and finally finished it in late November. While reading, I was reminded of something Michael Brecker once said, although I cannot recall which interview it was from. He said that he was grateful that Coltrane left this world without saying too much. There are no surviving practice records or methods left by Coltrane, and only a small number of interviews exist. For Michael Brecker, perhaps not being able to see behind the curtain of the Coltrane circus made it feel more mysterious.

Before reading Michael’s biography, I had felt the same way about him. Because the biography describes in detail how he became “Michael Brecker,” that sense of mystery may have diminished somewhat. Even so, I am glad that I read it. The knowledge I gained outweighs what was lost. The more I learned about Michael, the more I came to understand how vast the ripple of his artistic legacy truly is.

There were several moments in the biography that left a strong impression on me. One was when a fan told Michael, “I copy your solos all the time, I’m a huge fan.” Michael replied, “Thank you, but don’t copy my solos. If you copy the artists who influenced me, then we can become brothers.” I found this way of thinking fascinating. In other words, he was probably saying, listen to Trane and Joe Henderson. There were a few other moments that stayed with me as well, but as I write this now, I cannot quite recall them.

Music I listened to and transcribed

Following last month, October, I continued transcribing Cannonball Adderley’s “I Remember You” and “The Sleeper.” His time feel is incredible. I also listened frequently to Archie Shepp and Sonny Rollins. I feel like I listened to a lot of blues as well.

This year was one in which I intentionally distanced myself from Michael Brecker. It was a year spent learning from musicians who lived before him, searching for clues about what improvisation truly is.