-126-

The year began without my silent bass. On December 29th, I had taken it to Kurosawa instrument shop for a fingerboard extension and to have the fret markers filled in, leaving me to practice exclusively on bass guitar until January 18th. The guilt of not being able to practice on the silent bass never really faded, but spending some time focusing solely on bass guitar wasn’t a bad experience. Not only was I able to play phrases that would be physically challenging on the silent bass, but having frets also made it easier to visualize phrase shapes in my mind, which helped solidify the licks I was working on.

January was a month of major instrument upgrades. I originally started working full-time in logistics in Inzai, Chiba, in February 2024 to save up for a silent bass. Now that I’ve acquired most of the gear I wanted, I’ve decided to leave my job on February 26, 2025. Working full-time at a large corporation provides financial stability, but it makes it incredibly difficult to secure enough practice time. Right now, practice is my top priority. Moving forward, I’m considering a more flexible lifestyle, attaching a mini camper to the back of my bike (known as a bike camper in English), creating a space where I can live and practice while working part-time.

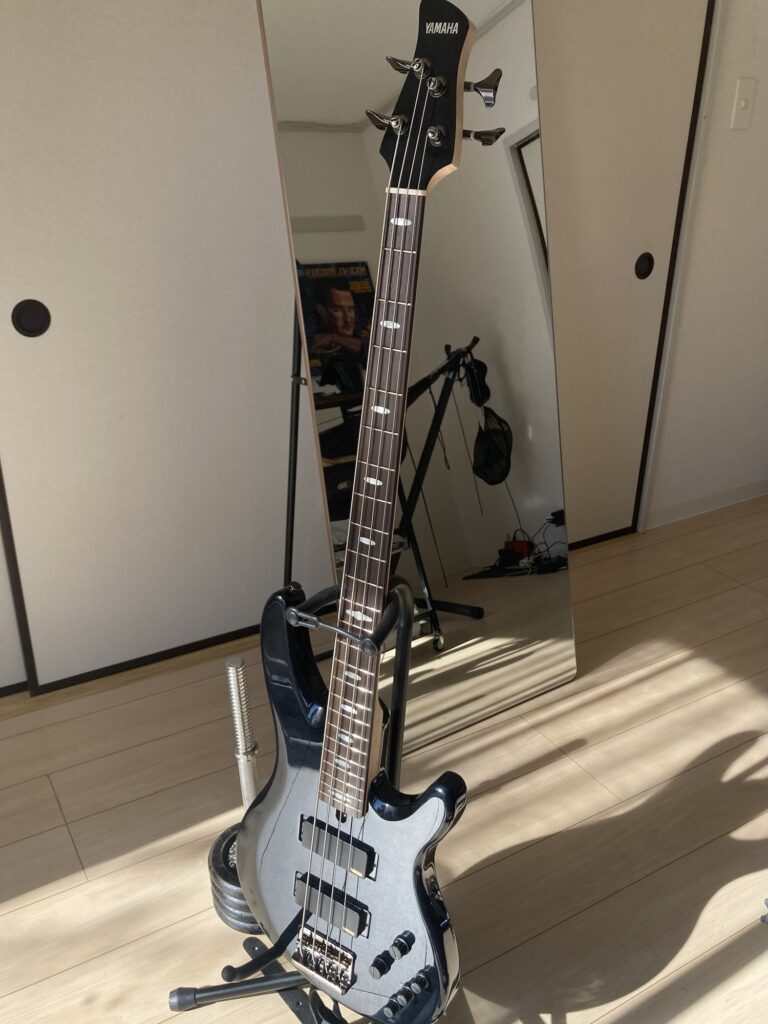

Getting back on track, I made three major gear upgrades this month. The first was purchasing a Yamaha TRB1000J. I first became interested in the TRB back in my university days when I started practicing jazz. I came across a video of Christian Eiwen playing a TRB, and I was captivated by its shimmering tone. I had considered getting a six-string model, but trying to learn both the silent bass and a six-string simultaneously would have been overwhelming. So, I opted for a four-string instead. The four-string TRB still shares some similarities with the left-hand shifting on the silent bass, and with 24 frets reaching up to high G, it offers good compatibility between the two instruments.

Another reason for the purchase was that I had been borrowing a bass guitar from a friend, a GrssRoots model, which is a Japanese-made Fender-style bass. Since it wasn’t mine, I couldn’t modify it as I wanted. I figured it was about time to own a bass guitar of my own.

The TRB has a bright tone with clear highs. I tend to prefer brighter-sounding basses over the darker tones of something like a P-bass. However, precision is crucial when pressing down on the frets, if my left-hand technique isn’t clean, the strings buzz easily, making fingering more challenging. In that sense, it requires as much left-hand control as a fretless bass.

The second upgrade was changing the strings on my silent bass from Helicore Hybrid to Spirocore Weich by Thomastik. I liked the core tone of the Helicore Hybrid, especially compared to the company’s Pizzicato Light Gauge, which had an artificially bright character reminiscent of D’Addario bass guitar strings. But after switching to Spirocore Weich, the sound became more defined and jazz-like. I love the crisp “click” sound when plucking the strings, it’s a signature trait of Spirocore Weich, adding a sense of airiness to the tone that really appeals to me.

Compared to Helicore Hybrid and Pizzicato, Spirocore Weich has lower string tension, making pizzicato easier to play. The moment I plucked the first note after stringing it up, I knew, this was the sound I had been looking for. At around ¥30,000 on Amazon, it’s quite expensive for double bass strings, but it was a meaningful upgrade.

The third upgrade was the fingerboard extension and position markers I had installed on my silent bass at Kurosawa instrument shop. Even before purchasing the instrument, I had planned to extend the fingerboard to improve the clarity of higher notes. When transcribing phrases from Coltrane or Michael Brecker, I sometimes encounter high C as the top note. I realized that when playing that range with my left-hand ring finger, there wasn’t enough space for my right-hand index finger to execute a proper pizzicato stroke. Even when I managed to pluck in that cramped space, the notes didn’t sustain well.

Through trial and error, I discovered that playing beyond high G on a double bass (above the 24th fret) produces better sustain when plucked closer to the bridge, where there’s no fingerboard. This led me to conclude that extending the fingerboard was necessary to allow for a clearer, more resonant high register.

Additionally, this modification unlocked a new approach, even in the lower range, I can now pluck over the extended fingerboard (closer to the bridge), giving me more tonal options. In a way, this upgrade feels similar to adding an extra pickup to a bass.

When I played pizzicato on the extended fingerboard, the tone became noticeably tighter and more focused, bringing me closer to the sound I had envisioned. The difference in sustain and clarity in the higher register is striking when comparing notes played on the original fingerboard versus the extended section. Without a doubt, this modification was the right choice.

For the shape of the extended fingerboard, I designed it by tracing the intended extension with a pencil. Initially, I thought extending it only under the G string would be sufficient, but I decided to extend it slightly under the D string as well. This way, when plucking the G string, my right-hand fingers can rest on the extended portion of the D string’s fingerboard.

Traditional fingerboard extensions used in classical music often extend all the way to the A string, but I found that unnecessary for my playing style. However, I did extend the E string side by about 1 cm. This allows my right thumb to rest at the very edge near the bridge, giving me better stability while playing.

For the fret markers, I chose brass. Initially, I had planned to use black mother-of-pearl, but ordering it online would have taken time to arrive, and there was also a risk that Kurosawa might not be able to process it.

When discussing materials for the markers, the staff at Kurosawa advised that a certain level of thickness was preferable. I felt that shell inlays might be too thin for the job. Aside from that, I personally like brass as a material, and I thought its subdued golden hue would complement the black fingerboard without standing out too much. I ordered 2mm brass rods from Amazon and took them to Kurosawa to have them installed.

Since the processing fee was the same regardless of the number of fret markers, I debated whether to add one at high C as well. However, I was concerned that having too many markers might feel restrictive rather than helpful, so I opted to embed only the essential ones.

As for the modification costs, the total came to ¥50,000; ¥40,000 for the harp-shaped fingerboard extension and ¥10,000 for the fret markers. The work took three weeks to complete. When I picked up the silent bass, I spoke with the repair technician, who mentioned that considering the labor involved, the ¥40,000 price for the fingerboard extension wasn’t really worth it for them. He said that moving forward, they would only take on similar jobs for ¥100,000 or more.

I had reached out to several other double bass (violin) shops, but the responses fell into two categories: either (A) they had never extended a fingerboard toward the bridge and couldn’t do it, or (B) they quoted me between ¥60,000 and ¥80,000. In that sense, Kurosawa gave me an incredible deal, and I’m grateful for their support.

Brian Bromberg and Branford Marsalis Interviews

In January, while struggling with the guilt of not being able to practice on my silent bass, I found myself binge-watching interviews of legendary musicians on YouTube. The ones that left the biggest impression on me were with Brian Bromberg and Branford Marsalis, both of whom emphasized that music should be played for the audience.

Brian, known for his insane technique and fiery bass solos, made a point that stuck with me: as a bassist, your job is to support the ensemble, being able to play impressive solos alone won’t get you hired. When I took a lesson from a professional bassist in New York last November, he told me the exact same thing. Since I tend to focus too much on bass solos, I want to keep this lesson firmly in mind.

Both Brian and Branford also highlighted that the bass is the most important instrument in an ensemble when it comes to generating rhythm. Contrary to popular belief, it’s not the drums that hold everything together, it’s the bass, which bridges harmony and rhythm. They both agreed that the bassist is the one connecting all the instruments in a band.

Branford, in particular, mentioned that he’s not looking for a bassist who plays wild saxophone-like solos. Instead, if he were hiring a bassist, he would choose someone with a strong internal pulse. That comment really stuck with me.

Brian also emphasized in every interview that he is a pitch freak. A440 is A440—not 442, not 438. He insisted that if a bassist hears their pitch drifting, they should immediately adjust their left hand to correct it. He also criticized the unspoken understanding among double bass players that slight pitch deviations in high positions are acceptable.

What shaped his thinking on this? He recalled watching a professional classical violinist, he couldn’t remember the name, who had massive, sausage-like fingers yet played Paganini flawlessly in the highest register of the violin, smiling effortlessly the whole time. That moment shocked him. If a violinist can do that with a hair-thin string, why should bassists have any excuse for missing intonation in high positions?

Hearing that made me realize I need to take high-register intonation much more seriously.

Branford Marsalis’ interview made me realize just how important it is to study jazz history. He shared a story about practicing while listening to a cassette tape of John Coltrane when Art Blakey walked in and asked what he was doing. Branford replied that he was trying to figure out how to play like Trane.

Blakey then asked, “Do you think Coltrane practiced by listening to a tape of his future self?” That question shifted Branford’s perspective—he started thinking about the musicians who had influenced Coltrane instead of just focusing on Coltrane himself.

Branford mentioned that if you play one of Coltrane’s early recordings for someone, many people wouldn’t even recognize that it’s him. He couldn’t recall the exact tune, but he emphasized that before Coltrane became obsessed with Charlie Parker, he was a huge fan of Johnny Hodges. According to Branford, many musicians who chase after Coltrane’s sound fail to see where its essence truly comes from.

That perspective was eye-opening for me. When I listen to Coltrane’s ballads, I can clearly hear that distinctive “pwaaah” phrasing—a direct influence from Johnny Hodges. Branford’s interview made me realize that getting closer to my musical heroes isn’t just about learning their phrases; it’s about studying the entire trajectory of their lives and influences from the ground up.

Music I Listened to This Month

This month, I’ve been listening to Two Blocks from the Edge by Michael Brecker. Since last year, I’ve been focusing on Brecker’s leader albums, but I had somehow missed this one. On YouTube Music, it’s categorized under the Michael Brecker Quintet, so it doesn’t show up when browsing Brecker’s main page—a frustrating issue that feels like a very millennial jazz fan kind of problem.

The title track, Two Blocks from the Edge, is all about Brecker’s solo—an absolute showcase of his power and speed that left me in awe. When studying Brecker’s playing, it’s easy to get caught up in his solos and lose sight of the bigger picture. But El Niño, another track on the album, stood out to me as a well-crafted composition in its own right, not just as a platform for soloing.