As December unfolds, I had expected the chill in Chiba to become truly biting, but looking back, it was November, marked by the seasonal shift, that felt colder to the body. While December’s average temperatures are indeed lower, the body seems to find its rhythm, adapting to the cold and even finding comfort in it. November, however, brought challenges: room temperatures hovered around 10°C, leaving my fingers stiff and cold during practice. To counter this, I introduced a Dyson air purifier with heating capabilities in December.

Winter has its quiet charms, no insects, clear starlit skies, and the absence of sweat, but it also comes with trade-offs. The lack of vitamin D from sunlight and the extra preparation needed to venture outside often make unplanned outings feel like obstacles. Without careful scheduling, I found that practice time could easily slip away.

1. Songs I’ve Listened to Often This Month (Moment’s Notice, Outrance, Don’t Try This at Home)

Moment’s Notice

This standard has been a central focus of my practice. I avoided listening to Coltrane’s original version, as I had already immersed myself in it extensively earlier this year, from February to April, during the process of transcribing his solo. Instead, I explored two other interpretations: one featuring Arturo Sandoval and Michael Brecker, and the other by Danny Grissett’s trio. Arturo Sandoval’s performance stands out for its commanding strength, holding its own alongside Brecker’s awe-inspiring solo. As for Danny Grissett’s trio, it’s not only Danny’s extraordinary sense of rhythm that captivates me but also the drummer’s rich musical vocabulary and nuanced use of dynamics. The drum solo, in particular, is so engaging that I find myself returning to it time and time again.

Outrance

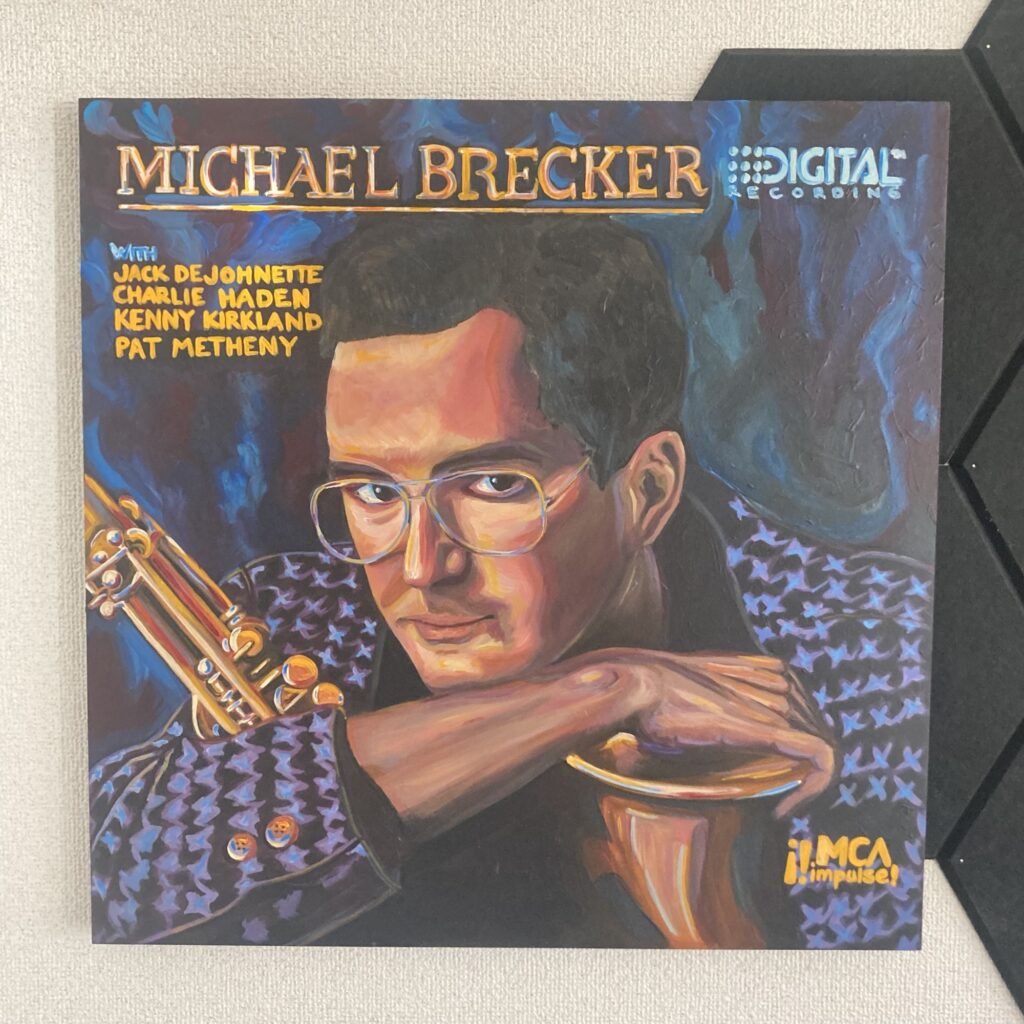

I discovered Outrance while exploring Michael Brecker’s leader album Time Is of the Essence. Brecker has a knack for placing unforgettable tracks, ones that leave listeners astonished, either as the final or second track on his albums. Never Alone from Wide Angles, Cabin Fever from Tales From the Hudson, and My One and Only Love from his self-titled album are all prime examples of this thoughtful sequencing. Similarly, Outrance lives up to its name, evoking the intensity of a fierce struggle. The interplay with Elvin Jones elevates the track, with Brecker channeling a profound depth of expression that feels even more impassioned than usual.

The piece centers around C minor and diminished scales, keys where Brecker seems to thrive. Of course, he delivers flawless solos in any key, but on fiery tracks like Peep or Cool Day in Hell, his explorations feel boundless, as if he has fully absorbed C minor to the point of transcending tonal limitations, delving into a freer, almost atonal form of self-expression.

In Time Is of the Essence (1999), Brecker’s sound carries a different kind of power compared to his Steps Ahead days or his 1987 Michael Brecker album. The density of his playing has increased, resulting in a rawer, more intense energy. That evolution is palpable here.

While Elvin Jones’ drumming might seem less overwhelming than his usual avalanche-like solos, it’s astonishing to hear him, at 71 or 72 years old, matching Brecker’s ferocious energy with such authority. Their performance together on Outrance is nothing short of a marvel.

Don’t Try This At Home

Don’t Try This At Home

Despite being the title track of Michael Brecker’s album, Don’t Try This At Home seems to receive less attention than some of his other compositions. On YouTube, for example, Itsbynee Reel from the same album has over 92,000 views, while Don’t Try This At Home lags behind with only 14,000, making it the second least popular track on the album. Of course, as any jazz musician would agree, the quality of a piece is not necessarily reflected in its play count. Considering its level of compositional brilliance, this track deserves far more recognition.

When I first heard it, I was completely thrown off. It was incomprehensible yet shocking in its complexity. Had I been cycling at the time, I might have found myself in an traffic accident. The title, Don’t Try This At Home, feels both ironic and fitting, as the music is far beyond anything one could casually replicate. In the middle section, Brecker’s long tones almost disrupt the rhythm, creating an illusion of detachment, but then Herbie Hancock steps in, maintaining the groove and launching into a sharp, incisive solo. The rapid modulations straight out of the head might explain why this track isn’t as accessible or “musical” to a broader audience, and perhaps that contributes to its lower play count. The difficulty in even humming the head makes this understandable to some degree.

As of January 2025, my listening habits consist almost entirely of Coltrane or Brecker, so I’m not sure what kind of universal impressions I’d have of other artists. Still, I value the initial feelings I had when I first heard their music: “I don’t understand this, and I don’t particularly like it.” That reaction, I believe, stems from encountering something beyond my current level of comprehension. Beneath that confusion often lies hidden brilliance.

For instance, when I first listened to Coltrane’s Crescent in October of last year, my brain couldn’t process it. The lack of immediate dopamine made it hard to enjoy, but the more I listened, the more I became captivated by its depth. In hindsight, this initial feeling of confusion and dislike might be a universal reaction for anyone encountering Coltrane or Brecker’s music for the first time. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most rewarding art challenges us to dig deeper, uncovering treasures hidden beneath the surface.

2. Triad Practice

Last month, after watching a interview video of Pat Metheny and reviewing my own playing, I realized the need to practice triads more seriously. Reflecting on it, I regretted not addressing this earlier. While I had worked on triads in the past as finger exercises and to understand the structure of keys, I had never focused on them as tools for soloing. Without a rhythmic vocabulary, my past self couldn’t imagine how to incorporate triads effectively into a solo. Instead, I gravitated toward arpeggios with their four-note structure (root, third, fifth, seventh).

Practicing triads opens the door to a wealth of skills. Not only does it help internalize scale tones, but the risk of sounding monotonous without attention to rhythmic phrasing forces an improvement in rhythm. However, practicing triadic inversions to outline chords is deceptively challenging. Initially, I thought arpeggios, with their four notes, would be harder than triads. In reality, having fewer options with triads demands more creative expression and the application of complex rhythmic language, placing a heavier load on the brain’s processing power.

For string instruments, triadic inversions come with an additional challenge: the root and fifth often form a fourth interval shape on fingerboard, making certain left-hand positions less ergonomic and requiring time to adjust. Compared to scales like diminished, where tones are closely spaced and easier to locate on the fingerboard, triads have wider intervals. Unless the triad shapes are fully internalized, finding the next note on the fingerboard becomes a slow process. This illustrates why triads are considered foundational. They demand thorough mastery before they can be played fluidly.

With dedicated practice, triads can elevate one’s level across rhythm, harmony, and technique. This, I believe, is why Bach’s compositions serve as excellent exercises for jazz musicians. The precision and balance required to navigate Bach’s music share a kinship with the challenges posed by triadic studies, making them an invaluable foundation for deeper exploration.

From a technical standpoint, mastering triads isn’t inherently difficult, but it requires a significant investment of time. When viewed from another perspective, the road to internalizing triads is finite; the patterns are limited to just 144 in total. There are four types (major, minor, diminished, augmented), each with three inversions. Practicing these across 12 keys gives us 3 × 4 × 12 = 144. For someone raised in Japan, where elementary school students are expected to learn around 1,000 kanji characters, memorizing 144 patterns might seem relatively simple.

However, the real challenge lies not in memorization but in applying these patterns instantly and contextually during performance. To execute triads effectively, I need to hear the notes in my head and immediately visualize them on the fingerboard. This difficulty applies to mastering any lick, but with triads, the wide intervals demand that the connection between auditory imagery and muscle memory be exceptionally precise.

This particular challenge is one reason I avoid five or six-string bass guitars. As the fingerboard expands, so does the number of triads and the relationships between notes, making the process of internalization even more time-consuming. Even on a four-string bass, understanding and organizing these relationships for just one note can take an extraordinary amount of time. While five- and six-string basses offer the option to cover desired notes through vertical movement of the left hand, the inevitable shifts between horizontal and vertical positions introduce their own complexities. Avoiding large shifts isn’t always possible, regardless of the number of strings.

The mastery of triads becomes a test of patience and focus, an exercise not only in technical fluency but also in organizing the mind to align hearing, seeing, and playing into a seamless whole.

3. Using the Moises App for Solo Analysis

In December, I spent more time practicing walking bass lines and began using the iOS app Moises, which features AI-powered audio separation. While I initially downloaded the app specifically for walking bass practice, I discovered it is also useful for solo analysis, transcription, and focused listening. For walking bass, removing the bass track allows for better connection with the rhythm section. However, this month, I started using Moises more for solo analysis and transcription. The shift came when I realized the app allows key changes.

Another discovery was the true function of the “➤➤” button that appears during playback. I had mistakenly assumed it was for skipping tracks, but it actually moves the track forward or backward by a few seconds. Once I understood this, it became an invaluable tool for solo analysis, enabling precise navigation through solos.

I consider Moises a revolutionary app among recent music tools. Over the past few days, I have been extracting solos from recordings and looping them in all 12 keys for immersive practice. The transposition feature is incredibly useful. For instance, I had grown tired of listening to Softly as in a Morning Sunrise in C minor, but Moises allows me to hear my favorite artists’ interpretations in every key. Additionally, high-quality backing tracks from YouTube, such as those from Phil Wilkinson Music, can be imported into Moises, making it possible to practice in all keys. Even familiar songs feel fresh when explored in 12 keys, offering new discoveries with each listen.

4. The Music I Listened to Most This Year

This year, I primarily focused on Michael Brecker’s leader albums. The following list isn’t just a collection of my favorite tracks (though I do love them) but rather songs I revisited repeatedly for analysis. The process often led me deep into the rabbit hole, making it hard to resurface.

- Inner Urge by Joe Henderson

- Moment’s Notice by John Coltrane

- Syzygy by Michael Brecker

- Recorda Me by Michael Brecker

- Crescent by John Coltrane

- Naima by Michael Brecker

- Impressions by Michael Brecker (McCoy Tyner)

- Nothing Personal (Live) by Michael Brecker

- Giant Steps by Michael Brecker

Without a doubt, the album I listened to the most was Michael Brecker’s Michael Brecker. I listened to it so much that I temporarily moved past sentimentality and nostalgia into a brief phase of fatigue. However, with the Moises app allowing me to hear these tracks in all 12 keys, I feel I could continue exploring this album for another 11 years without getting bored.

5. Gear Updates: Knee Pad and Double Clamp for the Silent Bass

In November 2024, I acquired a knee pad for my Silent Bass SLB300. Although it was designed for seated play, I’ve been experimenting with ways to adapt it for use while standing, allowing it to rest against my left knee.

After several attempts, I settled on using a double clamp, which allows both attachment points to rotate.

This feature enables fine adjustments to the angle, making it easier to find a comfortable and stable position. Additionally, by incorporating a lightweight guitar footrest for my left foot, I can achieve a posture that closely resembles seated play, even while standing.