-80-

In Chiba, Japan server, the season turned chilly seemingly overnight, erasing any trace of the lingering heat wave from weeks prior. With the daily temperature swing of ±10°C or more, I noticed an unexpected ±20Hz discrepancy on the tuner of my Yamaha SLB300, which I hadn’t anticipated would slip out of tune. This sharp seasonal shift also brings the challenge of balancing body temperature; my body warms quickly as soon as I begin practicing. But despite these seasonal adjustments, this month I’ve thankfully found myself deeply immersed in music once more.

To start off the month, I set out to fully understand my newly acquired Yamaha SLB300. I experimented with different fingerboard positions, exploring tones from near the bridge to closer to the neck, searching for the sound I had in mind. Much of my time has been dedicated to refining my right-hand technique through trial and error. I also picked up a budget computer for 9,000 yen, which I use with Catwalk and Scarlett Solo to record lines. Though it’s a bit sluggish, it works well enough for my needs.

To preserve this moment before memory fades, here are some of the key topics that have occupied my mind this month:

1 Ron Carter’s Pizzicato Technique

2. The Mystery of Elvin Jones in “Inner Urge”

3 Coltrane’s “Crescent”

4 “Mr. JJ” by Branford Marsalis and Michael Brecker

5 Alex Sipiagin’s Approach to the 4th

1 Ron Carter’s Video on Right-Hand Pizzicato Technique

In my quest to draw a strong sound from my silent bass, I’ve been focused on improving my right-hand pizzicato technique. In my research, I came across a video interview with Ron Carter, an absolute legend in the field.

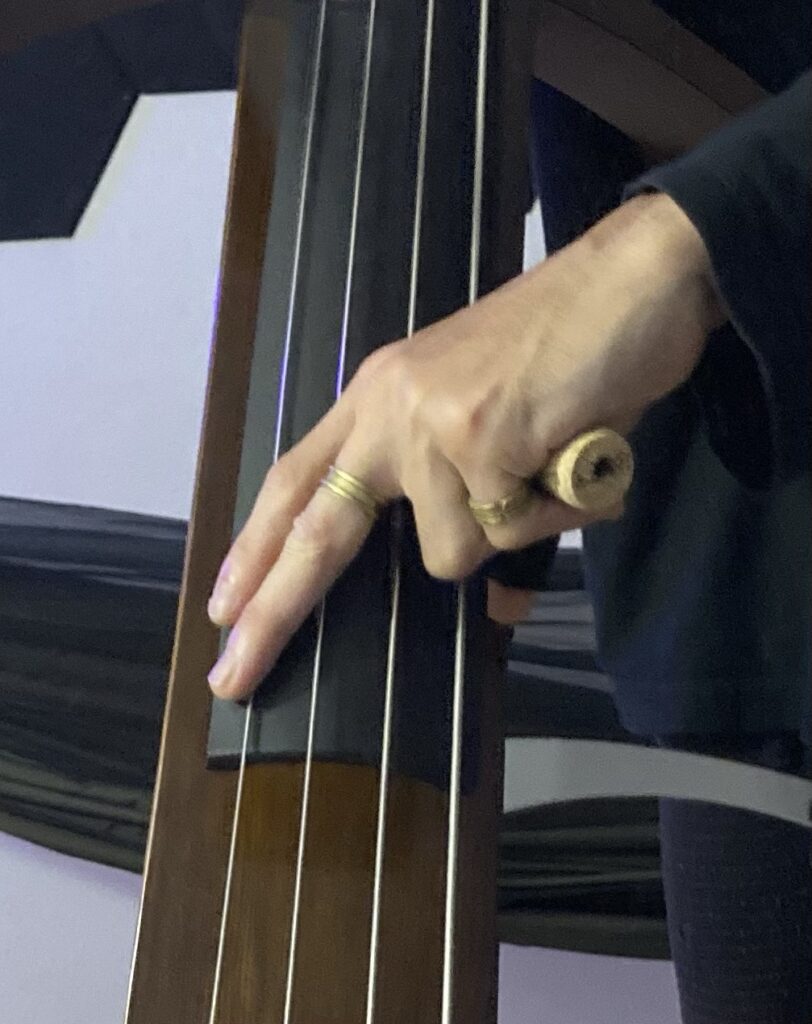

I’d heard that when virtuoso Marco Panascia took lessons from Mr. Carter, he learned to practice with his right thumb fixed to the bridge of his bass fingerboard using Velcro tape. In the video, Mr. Carter elaborates on how the pizzicato technique shifts in subtle but meaningful ways depending on hand position along the fingerboard. He explains that playing closer to the bridge, even with the same amount of force, can enhance the sound quality compared to playing closer to the neck with a firmer attack. Also he demonstrates that angling the fingers parallel to the strings, aligning the index finger with the middle, and using a straight joint to pluck with the index’s side gives a tone clarity. He also mentions an exercise using a wine cork held with the ring and pinky fingers to reduce unnecessary force, focusing instead on straight finger joints. While I usually pluck with my ring, middle, and index(was difficult to hold cork with only pinky), the exercise offers a valuable lesson in controlled power.

I attempted Mr. Carter’s Velcro technique to adjust my right hand’s configuration closer to the bridge, but the Velcro soon wore out. So I switched to clear plastic dots from the dollar store, which I could affix to the fingerboard for a more stable pivot point.

Though the dots became less sticky after about a week and a half, they had already done their job: I had adapted to placing my right hand near the bridge, and my ear had developed a clearer sense of my desired sound versus what I wanted to avoid.

Mr. Carter emphasizes the importance of experimenting with various fingerboard positions to find the sound one envisions. This approach reorients the focus from merely playing well to intentionally pursuing a specific tonal character—a reminder of the artistry beneath technique. Carter’s mindset of constant experimentation aligns with what Pat Metheny said in his interview: that listening is more crucial than playing. Beyond pizzicato, Mr. Carter describes his formula for ideal string height (pencil-width clearance), thumb placement under the D string, and slight left elbow elevation around the neck position.

In another Open Studio interview, he urges bassists to think like scientists, approaching the double bass as a field of endless physical variables to be tested and understood. I admire his scientific approach and his dedication to sharing knowledge through books and other media, which have influenced countless bassists worldwide. Not only is there a wealth of music available for streaming, but it’s astonishing how much firsthand insight into these jazz legends is now readily accessible online. I find myself immersed in this remarkable convergence of space and time.

2. The Mystery of Elvin Jones in “Inner Urge”

Lately, I’ve been listening to Elvin Jones’ solo in “Inner Urge” on loop.

Beyond studying his language, I became absorbed in a specific moment in “Inner Urge” where Elvin skips the final 16 bars, leading right back into the head. Such a choice, made without apparent warning, struck me as bold. How, I wondered, did Joe Henderson sense the sudden shift and respond seamlessly?

My thoughts were as follows:

- Premise: Elvin seems to skip 16 bars and immediately return to the head.

- During Elvin’s solo, McCoy Tyner introduced an F# chord, to which Joe Henderson responded instantly, seamlessly bringing the band back to the head.

Throughout the solo, Elvin subtly reintroduces rhythms from the theme, providing listeners with a familiar pulse even as he delves into intricate polyrhythmic textures. Therefore, it’s hard to imagine he’d spontaneously cut 16 bars without purpose, yet this only adds to the piece’s enigmatic allure. If my interpretation is correct, Joe’s instantaneous response showcases his remarkable ability to hear and process information quickly. I can’t help but wonder what his ear is made of. (Watch closely at 9:37 at 0.25x speed to see how McCoy plays F#, then Joe plays C.)

Regardless of interpretation, the power of Elvin’s solo is undeniable. I’ll be diving deeper into his artistry for some time to come.

3. Coltrane’s “Crescent”

Building on last month, I continued listening to Coltrane’s “Crescent,” which Brecker highlighted in an interview.

The name “Crescent,” derived from the moon’s shape, lends itself to a dark musical texture. Brecker’s comment—“Sound is just decoration; rhythm is what I’m always aware of”—resonated as I listened with particular attention to Coltrane’s rhythm. The number of notes, which he continuously plays to change colors, is overwhelming, but his typical rhythm is evident. The intricate phrases he weaves create a rhythmic clarity that feels like a language. This revelation brought me to a theory that rhythm in jazz might even mirror the English language itself. While perhaps tangential to the topic, I’m fascinated by the notion that human rhythm is rooted in both hardware and software factors. From a hardware perspective, our heartbeat provides a fundamental rhythmic pulse. However, for software aspect, our cultural environment, particularly language and its rhythmic patterns, also shapes our sense of time. This raises intriguing questions about how these factors might contribute to the diverse ways individuals from different cultures perceive and express rhythm. If Coltrane’s unique sense of time was influenced by his upbringing and the linguistic rhythms of his native language, I’d be eager to delve deeper into his background.

4. “Mr. JJ” by Branford Marsalis and Michael Brecker

In my search for interviews, I stumbled upon one where Branford Marsalis interviews Michael Brecker. Both men are physically imposing, reminiscent of basketball players. In fact, Brecker even aspired to play professional basketball in high school.

I looked in the comments section of this video and saw information about the two playing together in a song called “Mr. JJ”.

Later, I found a recording of “Mr. JJ,” and that night, the intensity of their playing left me mentally exhausted until morning. Branford’s sax has a slightly darker tone, with zigzagging phrases, while Brecker’s brilliance comes through in his upper-register climaxe licks (long notes) and rhythmic control. Drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts follows Brecker’s rhythmic vocabulary seamlessly. It’s interesting that “Mr. JJ” is included in the album “Bar Talk”. The album’s casual title does not match with the intense energy of this particular track.

5. Alex Sipiagin’s Approach to the 4th Degree

Listening to Michael Brecker’s “Wide Angles” album last month, I was captivated by Alex Sipiagin’s solo in “Scylla.” I followed more of his recordings, including his take on “Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise.”

He plays a solo from F on the 4th degree of a C minor chord. This approach intrigues me for its harmonic possibilities, as it allows for interpretations such as a melodic minor fourth (C-△ and F) or a tritone against a dominant chord (B7 and F). While I’ve yet to fully analyze it, his distinctive phrasing and tonal choices hold much to explore.