-103-

A Musical Journey Through November: Reflections and Lessons

In Inzai, Chiba, Japan, the daytime temperatures hover around 14°C—a subtle nod to the arrival of winter. Amid this seasonal shift, I’m grateful to have continued my journey in music this past month. November also marked a bittersweet farewell: on November 9th at 1:40 PM, I parted with the double bass I purchased back in January. It was an instrument I played often and loved dearly. Letting go was difficult, but I was comforted knowing its new owner would cherish and care for it.

Selling the bass online, I couldn’t help but wonder who might show interest in buying it. When the day came, I waited at a designated park, my curiosity growing. To my surprise, the buyer was a professional bassist from New York—someone with 15 years of experience playing alongside jazz legends. What are the odds that we’d cross paths in a quiet town like Inzai? Such a meeting felt extraordinary, and I seized the chance to ask him for a private lesson. He agreed without hesitation, leading to my first double bass lesson

1. My First Double Bass Lesson

When I heard him test the bass in the park, the first thing I noticed was the smoothness of the sound. There was no buzzing from the strings, and the resonance was even and natural. In contrast, my own playing often includes the percussive sound of strings hitting the fingerboard, which disrupts the dynamics. I had assumed the issue lay in the low action of the strings, but I later realized this was a misunderstanding.

We held the lesson in a park near his home in Yokohama, which required careful planning given the distance between Chiba and Kanagawa. While I considered meeting in central Tokyo at community centers, studios, or karaoke rooms, the hassle of making reservations led me to propose traveling to Yokohama instead. I also wanted to experience transporting my silent bass by train and on foot.

Transporting the silent bass turned out to be more challenging than I had anticipated. The bass itself weighs 6.8 kg, and with the case, it totals around 10 kg—comparable in weight to a double bass. The difficulty of carrying it varies depending on which part of the case you hold. On a previous occasion, I used the included strap and carried it on my shoulder from the store to my home. After just 20 minutes, fatigue began to settle in around my shoulders.

Hoping to distribute the weight more evenly, I experimented with wearing it like a backpack using double straps. However, this proved just as demanding as the single strap. It reminded me of mountaineering in snowy landscapes, where every step requires deliberate effort. The bottom of the case repeatedly bumped against my calves, making walking awkward. Despite adjusting the strap placement through trial and error, I couldn’t find a truly comfortable way to carry the case. For my next attempt, I’ve decided to place it on a trolley cart, letting the wheels bear the load instead.

The park itself was expansive, and while the forecast called for a 40% chance of rain, there was no shelter in sight. I set my gear on a stage-like platform and waited.

When he arrived 30 minutes later, we greeted each other warmly, and the lesson began at 3:15 PM. We talked and played continuously until dusk at 5:30 PM, engaging in an unbroken exchange of questions and answers.

I was deeply impressed by insights he shared about life as a musician in New York and his profound understanding of rhythm—perspectives you won’t find on the internet. Even foundational concepts that might seem like common knowledge gained a fresh, practical clarity when coming from him. For instance, regarding right-hand technique, I noticed that he used the weight of his entire shoulder and arm to pluck the strings. This wasn’t something he explicitly taught me, but observing his right hand up close made it evident.

Having started on electric bass, I had developed a habit of relying on a downward flick of the fingers to produce sound. While I had previously grasped the idea of using arm weight in theory and practiced it, I had never fully embodied it. Comparing his approach to mine revealed a distinct difference. My right hand relied on building acceleration just before and through the moment of contact with the string, akin to swinging a bat and following through after striking the ball. In contrast, his technique involved generating momentum from a near-static position, almost as if his fingers were poised on the edge of the string, waiting to release energy—reminiscent of a judo throw, where momentum is added at the very moment of contact.

This contrast taught me something profound: the act isn’t about “plucking” the string but rather “grasping and releasing” it with intention.

His insights, drawn from years of working in New York, were deeply resonant. He emphasized the importance of listening—not just hearing, but truly connecting with others in an ensemble. For instance, he explained that while matching rhythms with a drummer might create the illusion of a groove for the audience, true synergy requires a deeper, mutual connection.

I asked how he managed the pressure of performing in New York’s high-stakes environment. His answer was profound: instead of focusing on his own note choices, he shifted his mindset to listening and reacting to those around him. This shift allowed him to overcome his nerves and embrace the

One practical takeaway was his approach to rhythm practice. He demonstrated a method of setting a metronome below 40 bpm and focusing on the space between notes while playing open strings. It sounded simple in theory, but mastering it was a different story. Reflecting on his time at Berklee, he admitted he should have prioritized foundational skills like rhythm and walking bass lines earlier in his career—a lesson I took to heart.

Although he has since returned to New York, the experience reinforced the value of learning directly from another person. The knowledge gained through human interaction lingers in a way that internet searches never can.

2. The Game-Changing App: Moises

After the lesson, I became more attuned to my role as a bassist in an ensemble. He recommended practicing walking bass lines alongside drum tracks, suggesting apps like Drum Master. This inspired me to experiment with the app Moises, which allows for instrument separation within tracks.

The features of Moises never fail to astonish me. It’s a remarkable time to be a musician. I can’t help but imagine how jazz legends of the past might react if they encountered tools like iReal Pro or Moises. Would they embrace them with uncontainable excitement, or dismiss them as heretical shortcuts? Personally, discovering Moises felt like stepping into the future. I genuinely believe that in the not-too-distant future, we’ll be able to jam with AI, asking it to craft a solo that blends the essence of Michael Brecker and Joe Henderson into a perfect synthesis—and it will deliver.

There are two features of Moises that stand out to me as truly groundbreaking.

The first is its ability to isolate instruments within a track using AI. With this tool, I can separate Elvin Jones’ drum comping and practice alongside it. It allows me to rehearse with grooves from legendary drummers like Philly Joe Jones or Max Roach, immersing myself in their rhythmic nuances. But it doesn’t stop there—Moises lets you experiment with listening in entirely new ways. You can focus solely on the interplay between a soloist and drums, or between a soloist and piano. These combinations shift your listening perspective and often reveal subtleties you might never have noticed before, leading to fresh discoveries.

The second is the Smart Metronome, which automatically adapts to changes in tempo within a track. It’s a game-changer for practicing walking bass lines, especially when the rhythm becomes intricate and challenging. While it’s incredibly helpful for most situations, its precision does waver when faced with something as complex as Elvin’s drum solos or a soloist experimenting with polyrhythmic licks. Still, it offers a glimpse into how technology is reshaping the way we practice, learn, and ultimately connect with music.

Interviews with Joe Henderson, John Scofield, and Pat Metheny

I make it a point to watch at least one interview video every day, and this month, two interviews left a lasting impression on me. The first was with Joe Henderson and John Scofield. Although I watched it earlier in November and have since forgotten some of the details, a few of their insights struck a deep chord.

One of the most compelling points they discussed was the difference between how jazz was learned in the past compared to today. In an era when information was scarce, the process of learning was one of exploration, trial, and error—a journey that shaped the individuality of the musician. They spoke about the value of actively seeking out mentors, asking questions, slowly building a collection of cherished records, and listening to songs over and over. This deliberate and personal approach to learning gave rise to a unique sound in every player.

They also noted that today’s younger jazz musicians face a different challenge. With an overwhelming abundance of information, a strong sense of self—what Joe referred to as a “strong sense of who you are”—is essential to avoid being swept away in the current. Without this anchor, it becomes difficult to cultivate an individual sound.

I resonate with this idea deeply. In today’s world, escaping the deluge of information is nearly impossible, and I believe this has a negative impact on the formation of identity. The internet, with its layers of propaganda, ideologies, and marketing strategies, can easily consume you, making it all the more difficult to build a clear and authentic sense of self.

The other interview was with Pat Metheny. What stood out to me was not only his unwavering dedication to music but also his logical, analytical approach to it. Every story he shared was fascinating, from his time working with Jaco Pastorius before Jaco became a household name, to his insights on chord progressions and how he visualizes them through triadic inversions to outline the harmony.

One particularly compelling moment came around the 41-minute mark when he discussed the construction of melody. Metheny explained that by developing motifs in a way similar to the structure of “Happy Birthday,” musicians can create melodies that are far more distinctive and memorable. He also mentioned several musicians renowned for their skill in developing motifs, including Ornette Coleman, Lester Young, and Wes Montgomery. The way he connected these ideas to the essence of musical storytelling left a lasting impression on me.

He also mentioned that Thelonious Monk’s compositions never grow tiresome, no matter how many times they are reinterpreted through improvisation—a sentiment I wholeheartedly share. Take Round Midnight, for example; it feels like an eternal masterpiece, endlessly open to exploration without ever losing its allure.

Gear Updates (SLB300 Knee Pad, BOSS Wireless System, HIFIMAN Sundara)

This month, I made a few small but notable purchases. The first was a knee pad (BKS2) for my silent bass (SLB300), something I had been curious about since I first bought the instrument. The SLB300’s slim body design makes it difficult to support against the left knee when playing in a standing position. To address this, I acquired Yamaha’s official knee pad.

As I had suspected, the knee pad didn’t align properly with my knee when playing standing up, at least not without some modifications.

I’m currently working on customizing the knee pad to improve its fit with the instrument. I plan to explore this topic further in a future blog post, once I’ve refined the solution.

The second purchase was the BOSS WL-20L, a wireless device that connects instruments to amplifiers. While the SLB300 doesn’t often stray far from the amp, making a cable sufficient for most situations, this device proves incredibly useful when playing bass guitar. The freedom from cables is liberating—a small but significant improvement to the playing experience.

That said, it does come with a couple of drawbacks. First, I chose the WL-20L model specifically because it’s designed for active basses, but when switching the SLB300’s active circuit from off to on, the sound cuts out entirely. Second, when used with a passive bass, the tone leans noticeably brighter compared to a traditional cable. This is because the WL-20L lacks cable-tone simulation, which replicates the slight attenuation caused by a physical cable. As a result, the device works best with active instruments that already have built-in preamps, where cable-induced tonal shifts are negligible.

For passive basses, the brighter edge in the high frequencies gives it a distinct tone that I find intriguing, but it’s not ideal for recording purposes. Still, there’s something refreshing about this unique sound—a reminder that imperfection often brings its own charm.

The third purchase was the Hifiman Sundara, my first pair of open-back headphones. While the sound quality is slightly better than my consumer-grade Bose QC35 II, it didn’t leave me astonished. To go further in audio fidelity would require an amp—something I’m hesitant to explore, knowing how deep the audiophile world can get.

What I do appreciate is how the open-back design allows me to hear the natural resonance of the SLB300 while playing. However, after getting used to the cable-free convenience of the Bose, the dangling wires of the Sundara feel cumbersome. For casual listening while working around the room, having to carry both my phone and the wired headphones feels like a step backward.

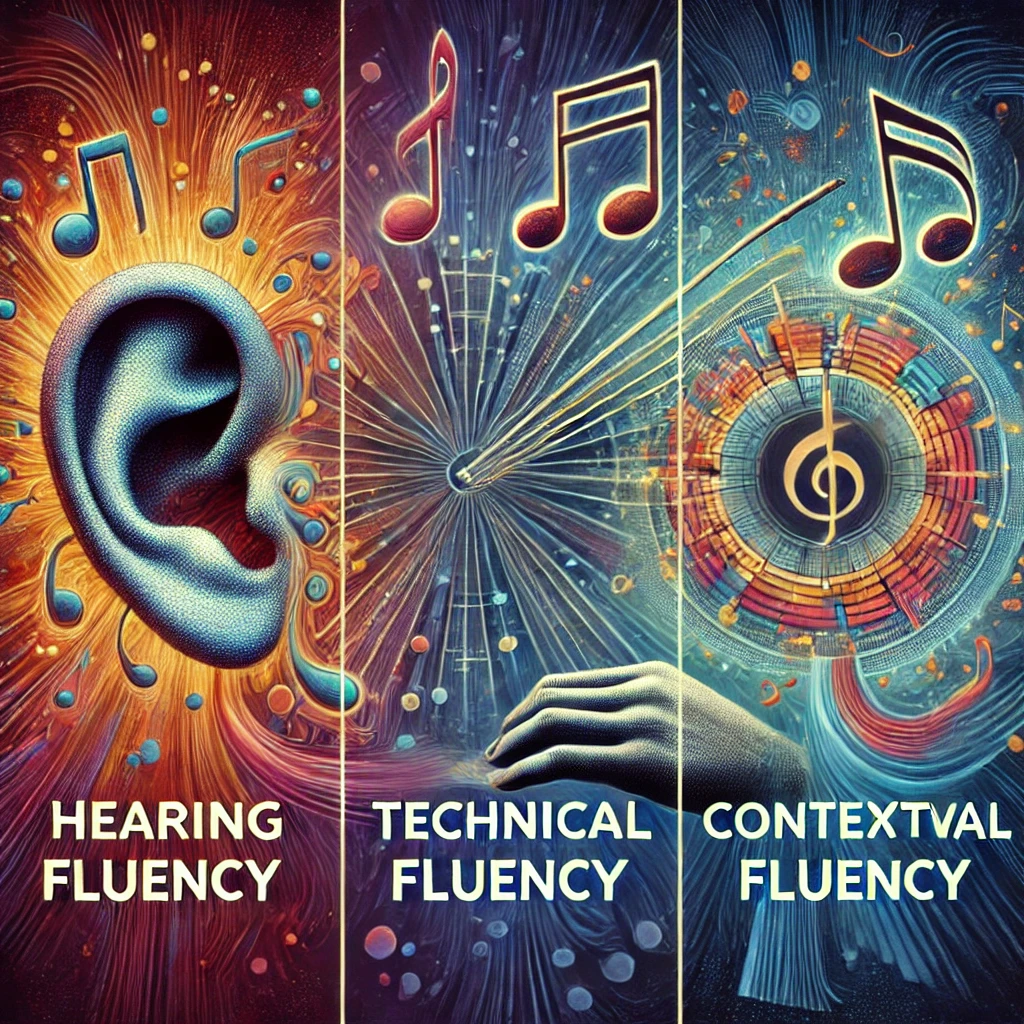

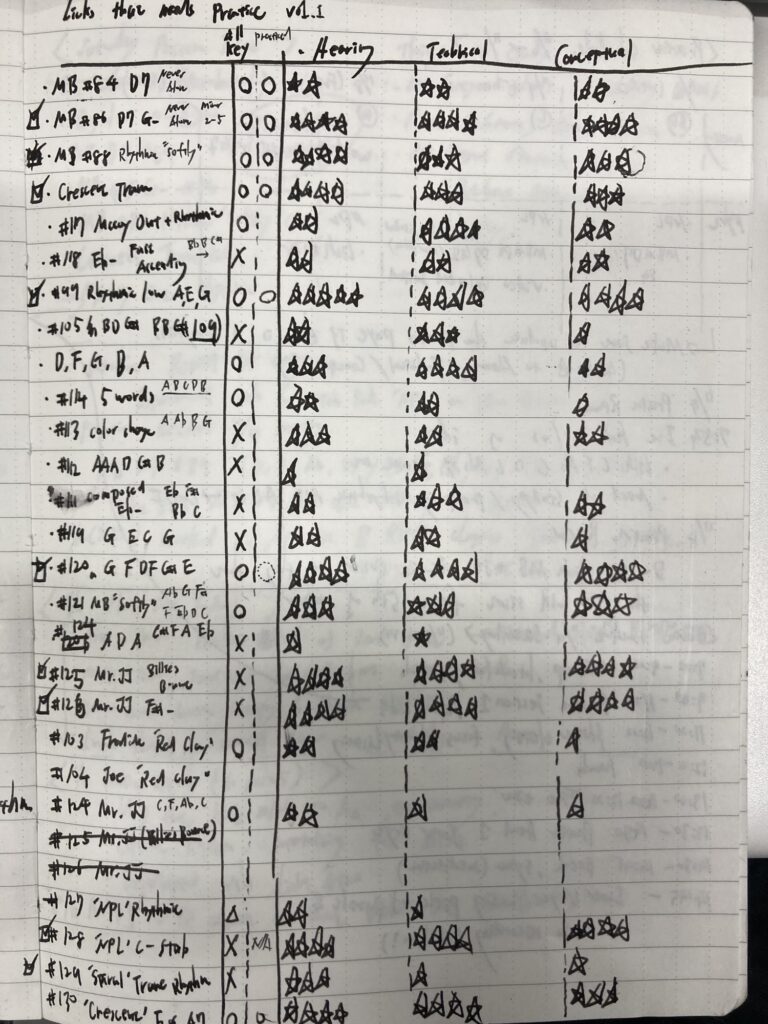

4. How to Assess Mastery of a Lick

Determining when to stop practicing a specific lick has always been a challenge for me. Is it enough to run through all 12 keys once? Should I stop after playing it a few times in a specific standard? Or should I aim to recall and reproduce the lick in all 12 keys within a second in my mind? To bring some clarity to this, I developed a personal system this month—a way to measure the degree of mastery for a lick by breaking it into three key aspects:

i. Hearing Fluency

This measures how clearly I can recall and hear the lick in my mind. I consider this the most important of the three aspects. For example, if I need to refer to sheet music or listen to the lick again to recreate it mentally, I would rate my fluency as ★1. On the other hand, if I can effortlessly hear the lick in my head across all 12 keys, I’d rate it as ★5. I consider a rating of ★4 or higher as sufficient to move on from practicing that lick.

ii. Technical Fluency

This aspect evaluates how smoothly I can execute the lick on my instrument. As a double bassist, this comes down to whether I have internalized the left-hand and right-hand fingerings. If I can imagine the lick but can’t physically play it, I would rate my fluency as ★1. If I can fluidly play the lick across all 12 keys, seamlessly navigating various positions from the lowest to the highest register of the double bass, it would earn ★5.

iii. Contextual Fluency

This measures how effectively I can apply the lick to different chord progressions. Even if I’ve achieved hearing and technical fluency, if I’ve never applied the lick in the context of a standard, I’d rate it as ★1. On the other hand, if I’ve practiced incorporating the lick into a variety of standards and progressions, it would earn ★5.

Using this system, I’ve started listing and categorizing the licks I’ve transcribed, making it easier to visualize my progress and identify areas for improvement. It’s a small yet meaningful step in bringing structure to my practice.

5. Songs I Listened to Often This Month

This month, I found myself returning frequently to Impressions by McCoy Tyner, featuring Michael Brecker. Brecker’s solo on this track is particularly fascinating when you focus on rhythm. His use of triadic rhythmic variations feels abundant and inventive, and his development of motifs is even more remarkable than usual. Each phrase connects seamlessly to the next, like sentences in a beautifully crafted narrative.

It’s a treasure chest of licks—so much so that transcribing the solos of both McCoy and Brecker would be an overwhelming task. Even so, it’s a song I enjoy singing along to during my morning bike commute. In early November, I alternated between Mr. JJ and Impressions as my soundtrack for the ride to work, and both became morning staples.

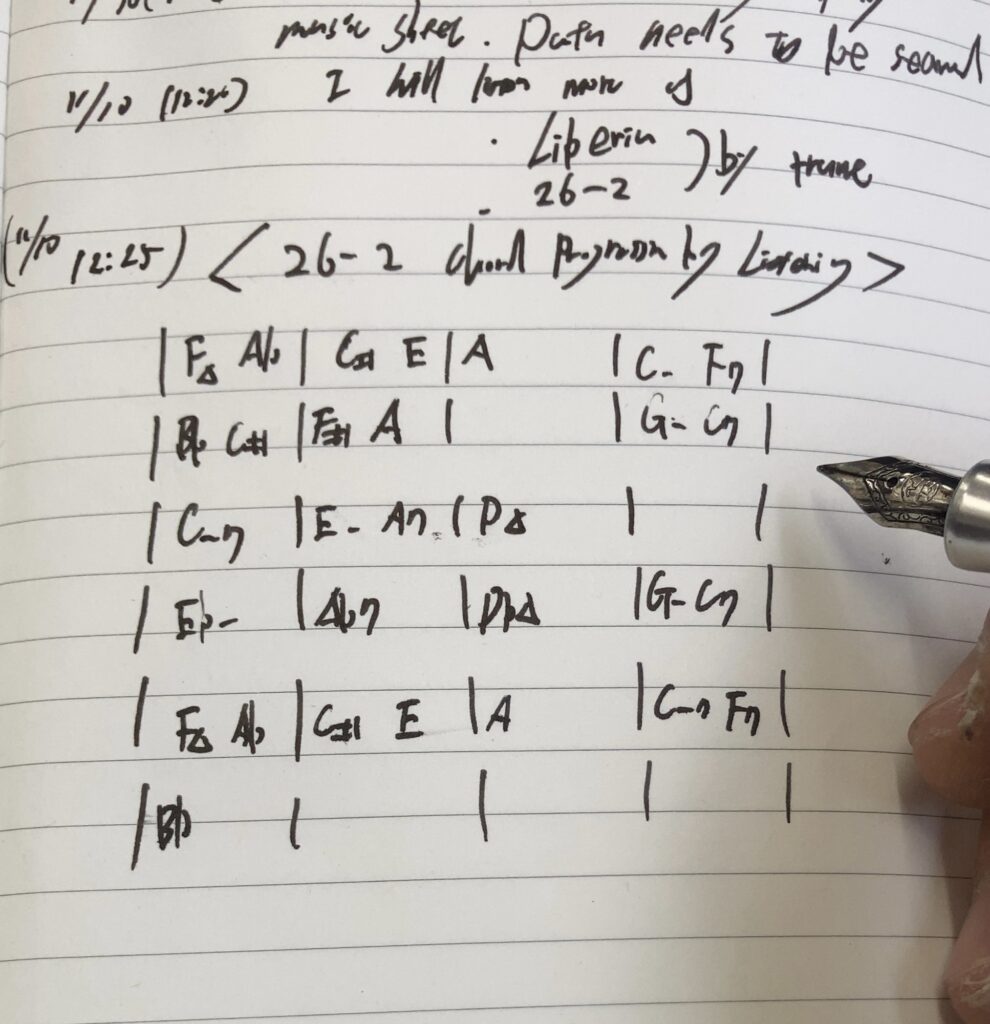

On the train to a lesson, I listened to Coltrane’s26-2for the first time. The chord progressions intrigued me, so I decided to transcribe it without looking at the changes. The process felt like solving a puzzle or working through a Sudoku—a satisfying mental challenge.

I’ve also been captivated by Elvin Jones’ drum solo on Black Nile. At first, the chaotic rhythms seemed indecipherable, but as I kept listening, I began to hear where the first beat of each measure landed. Once I anchored myself to that beat in my mind, the polyrhythms’ structure started to reveal itself. It’s a fascinating experience, akin to adjusting your eyes in the dark until the surroundings gradually take shape.

Finally, I’ve been listening daily to the live version of Nothing Personal since mid-August, often during my morning routine. Each time, I discover something new in Brecker’s solo. Recreating it on the double bass has been a rewarding challenge—it requires navigating from low to high positions, making it excellent practice for finger placement and technical fluency.